What I want to say isn't there! : Communication autonomy

20 October 2014

As an ILC Tech speech pathologist, one of the most important concepts I often need to teach others when I’m talking about augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) is ‘communication autonomy’. What does the person want to say? Do they have access to the vocabulary to say what they want to say, when they want to say it? Or is the vocabulary you have given them based on your ideas of what you think they should say, when you give them the opportunity to say it?

The best illustration I have seen to demonstrate this concept was from Gayle Porter (2010). It went something along these lines:

If you could be doing anything you’d like right now, anything other than sitting here reading this blog post, what would you like to do? Ponder that thought. Pick something. Anything. Now scroll down….

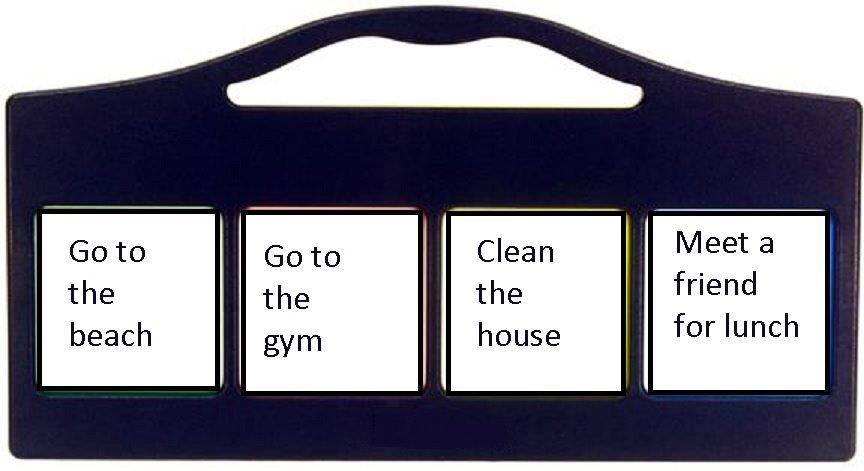

Here are your choices:

What did you choose? Surely, there was something close to what you were thinking? No? Did you choose something, or did you refuse to choose? If you didn’t make a choice, then you decided not to ‘compromise your communication autonomy’.

Burkhart and Porter (2010) define communication autonomy as “being able to express self in accordance with own communicative intentions” – saying whatever YOU want to say. Often when speech pathologists and others are choosing or developing an AAC system for an individual, they need to take into account the number of symbols that person can physically, cognitively and visually access. Many people believe that ‘simple’ choice-making is the place to start because it is concrete, and individuals can learn to discriminate between the symbols more easily. They mistakenly believe that it is easier for someone with cognitive challenges to choose between let’s say, three symbols to make a choice, than to communicate a message of their own intent. Yet, to do this means that the person has to:

- change their communication intent to match what you think it should be (ie. choice making)

- visually examine and discriminate between the symbols you have provided at that moment in time (often when people are providing 3 symbols at a time, they do this for a few different scenarios so the symbols come and go – they may not even be in the same position they were last time you put them there),

- and then do something to indicate the one they want (be it touch, look at, pick it up and give it to someone).

And all this time, they may have been thinking, ‘I’m tired’ or ‘wow, look at that sparkly necklace she’s wearing’. Yet, often times, if the person does not make a choice, it is assumed that they can’t. Perhaps they are the kind of person who wouldn’t compromise their communication autonomy – or didn’t know that perhaps they ought to – that you would think they were more clever if they just made a choice.

Another aspect of communication autonomy that we need to consider is who decides what reasons for communicating are most important to that individual. Who decided that indicating a preference or requesting an item would be the first thing that they would want to communicate? Yet so often, this is the first set of vocabulary provided to an individual. When I think back to my own daughter developing language, I recall that one of the first things she said was ‘hi dadada’, motivated by a desire for connection with her daddy, what we speech pathologists call ‘establishing and maintaining social closeness’. When we focus too much on choice-making and requesting, we neglect one of the most important purposes of human communication.

When we limit individuals access to a robust, comprehensive vocabulary – words that can be modelled for them to use to say what they want to say, whenever they want to say it – we are being what some have termed ‘the gatekeepers’ to augmentative and alternative communication systems. We need to presume competence and ensure individuals have access to an environment rich in language represented in ways they can learn to use, and that these methods are frequently used in natural contexts by those around them. And, if we need to provide ‘choices’ for individuals to select from, then please, ALWAYS give them a way out. Give them the option of ‘something else’ on that choice making display.

To find out more:

- Porter, G. and Burkhart, L. (2010). Developing Habits for Communication Autonomy and Accessibility. Workshop Presentation. ISAAC Conference, Barcelona. http://www.lburkhart.com/hand_ISAAC_B/Habits_for_Autonomy_Accessibility_hand.pdf

- PrAACtical AAC. Mar 26, 2014. Opening the Gates. http://praacticalaac.org/praactical/opening-the-gates/

- Uncommon Sense. Jun 3, 2013. The Gatekeepers. http://niederfamily.blogspot.com.au/2013/06/children-with-complex-communication.html

Translate

Translate